The prime rate is the interest rate that banks charge their best customers. It’s commonly used as a basis for determining rates for other types of loans, such as credit cards, lines of credit, mortgages, commercial real estate loans, and hard money loans. Typically, it’s 3% higher than the federal funds rate, a figure that is determined by the Federal Reserve.

Banks can use varying methods for determining what prime rate to use, but the most commonly used figure is the Wall Street Journal prime rate. Customers that represent the lowest risk of defaulting on a loan have the best chance of qualifying for the prime rate. Knowing what it is can give you an idea of the range of rates you can expect to see from lenders.

How the Prime Rate Works

As a general rule of thumb, the prime rate is typically 3% higher than the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate that banks charge other institutions to borrow money. In other words, just like individuals and business owners are charged interest when they take out a loan, banks are charged interest at the federal funds rate.

The Fed determines the federal funds rate based on the overall health of the economy. When the rate is reduced, it makes it more affordable to borrow money and encourages more spending. With a higher rate, borrowing money becomes more expensive.

Effects of a Rate Change

The Fed can increase rates if it believes inflation is running too high, or otherwise wants to reduce the flow of money between individuals and businesses. Loan rates will be higher, but rates on savings accounts will also be greater. In other words, increases in the federal funds rate and prime rate make it more expensive to borrow money and give people more incentives to save.

On the other hand, reductions in the federal funds rate generally occur when the Fed wants to encourage individuals and businesses to spend more money and increase hiring levels. Rates on loans will decrease, making it cheaper to borrow money. Similarly, rates on savings accounts will also go down, encouraging people to spend or invest funds elsewhere.

How Often the Prime Rate Changes

There is no set schedule for when the prime rate changes. However, it could potentially change around eight times a year. That is the number of times that the Fed typically meets to determine whether adjustments are necessary to the federal funds rate, although additional meetings can be called depending on the state of the economy.

Changes in the federal funds rate often lead to changes in the prime rate. While banks can choose which figure they use here, most use the Wall Street Journal prime rate. This rate is determined by surveying 30 of the largest banks and changes when at least 23 make a change.

How the Prime Rate Affects You

As a borrower, the prime rate is a large determining factor of the interest rate you’ll get on a loan. The more well-qualified you are, the closer your rate will be to the prime rate. One common determining factor is a credit score, where lower scores will have the greatest number of percentage points added to the prime rate.

You may want to view our list of other small business loan requirements for items lenders can use in evaluating what rate you qualify for.

If you have a loan with a variable interest rate that is tied to the prime rate, you could also see your monthly payments fluctuate if the prime rate changes. As the prime rate goes down, you could see your payments decrease. Similarly, if the prime rate increases, your required minimum payments could go up.

Loans with a variable interest rate will often have terms that specify when the changes can occur. Many also have limitations on the minimum and maximum rate you can get, regardless of the prime rate.

Below is an example of the rates a lender might offer based only on your credit score.

Borrower Credit Score | Example Prime Rate | Margin | Total Interest Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

760 to 850 | 8.00% | Prime + 0% | 8.00% |

720 to 759 | 8.00% | Prime + 1% | 9.00% |

680 to 719 | 8.00% | Prime + 2% | 10.00% |

620 to 679 | 8.00% | Prime + 3% | 11.00% |

Although the prime rate is largely responsible for determining the rate you can get on a loan, other factors, such as your credit score and business finances, play an important role as well. Our guide on how to get a small business loan contains recommendations on what you can do to improve your chances of getting a low rate.

Historical Prime Rates

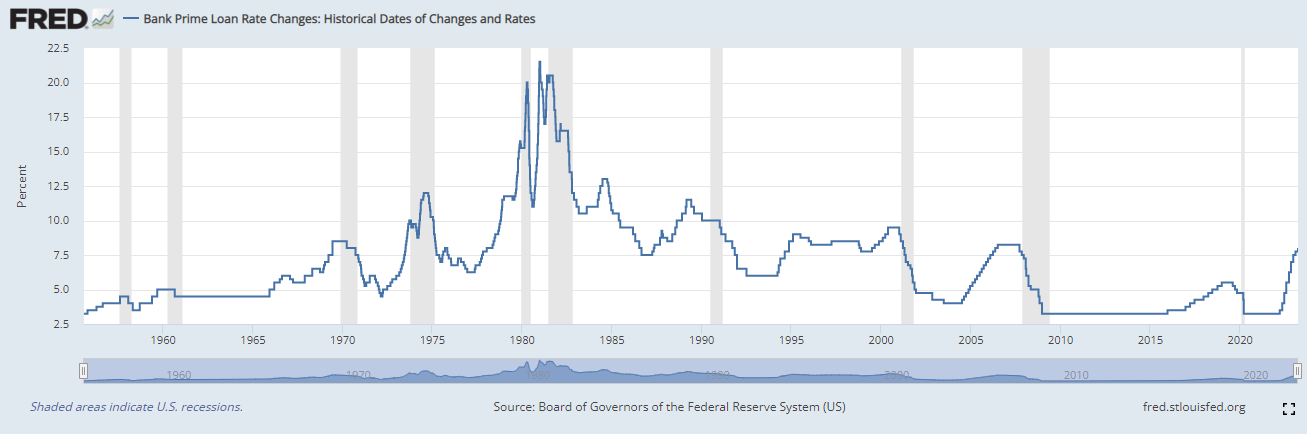

The prime rate will continue to change over time depending on the overall state of the economy. It reached a high of 21.5% in December 1980 and a low of 3.25% as recently as March 2020, which was largely in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We’ve listed the prime rate changes since March 2020, along with a historical chart dating back to the 1950s.

Date of Change | New Prime Rate |

|---|---|

May 4, 2023 | 8.25% |

March 23, 2023 | 8.00% |

Feb. 2, 2023 | 7.75% |

Dec. 15, 2022 | 7.50% |

Nov. 3, 2022 | 7.00% |

Sept. 22, 2022 | 6.25% |

July 28, 2022 | 5.50% |

June 16, 2022 | 4.75% |

May 5, 2022 | 4.00% |

March 17, 2022 | 3.50% |

March 16, 2020 | 3.25% |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Bank Prime Loan Rate [DPRIME], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PRIME, April 24, 2023

Prime Rate Alternatives

The prime rate is not the only figure that banks can use as a benchmark in determining how they set their interest rates for lending or banking accounts. Alternative figures can be used depending on a bank’s goals, policies, or location. This can be especially true for banks that have a larger international presence, as opposed to one primarily based in the United States.

Below are some examples of alternatives that banks may use:

- Secured overnight financing rate (SOFR)

- American Interbank Offered Rate (AMERIBOR)

- Bloomberg Short-Term Bank Yield Index (BSBY)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Yes, you might see this if you have a loan with a variable interest rate. The specific terms of your loan will indicate whether your loan’s interest rate is tied to the prime rate, how often it can change, and by how much. Loans with a fixed interest rate will not be affected.

There are no limits as to how high the prime rate can be increased. However, the highest rate ever recorded was 21.5% in December 1980.

The federal funds rate is determined by the Federal Reserve and reflects the rate that banks charge when borrowing money from one another. Meanwhile, the prime rate is typically 3% higher than the federal funds rate and is the rate that banks charge their customers.

Bottom Line

Being aware of the prime rate is important because it often impacts the interest rate you get on a wide variety of loans. It’s typically the rate offered by banks to its most creditworthy customers. However, while it may be one of the more common benchmarks banks use to determine rates, lenders can choose other options.