Journal entries are the fundamental building blocks of accounting. All accounting transactions start with a journal entry, the only way to record transactions in the books. Accounting journal entries are crucial in establishing a paper trail for transactions. Each journal entry must affect at least two accounts with total debits and credits balanced. In this article, I’ll show you how journal entries work and why it’s important to understand them amid the popularity of accounting software tools.

Parts of a Journal Entry

The simplest form of a journal entry has one debit and credit entry. However, a journal entry must also contain a date, posting reference, and description to keep accounting records organized and traceable. Below is a sample structure of a journal entry.

Journal | Page 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Date | Description | Post. Ref. | Debit | Credit | |

Aug. | 25 | Account to Debit | 1001 2002 | 10,000 | |

Account to Credit Journal Entry Description | 10,000 | ||||

- Date: This must be the date of the transaction, not when it was entered in the journal.

- Journal Entry Description: This line item briefly describes the purpose of the entry.

- Posting Reference (Post. Ref. or P.R.): This shows the general ledger account numbers of the accounts debited or credited. The bookkeeper usually fills out this section when posting journal entries to their respective general ledger accounts. For example, you debited Cash for $10,000. In the chart of accounts, the account number of Cash is 1001. After posting the $10,000 debit to Cash in the general ledger, you should enter 1001 in the posting reference column corresponding to the debit entry.

- Debit and Credit Entries: These line items should state the affected accounts in the transaction. The credit entries are always indented to the right, and all debit entries are listed prior to the credit entries.

But before the age of digital tools and electronic spreadsheets, businesses and accountants had to enter journal entries manually in a columnar notebook. Below is an example of how journal entries looked in their “ancient” form.

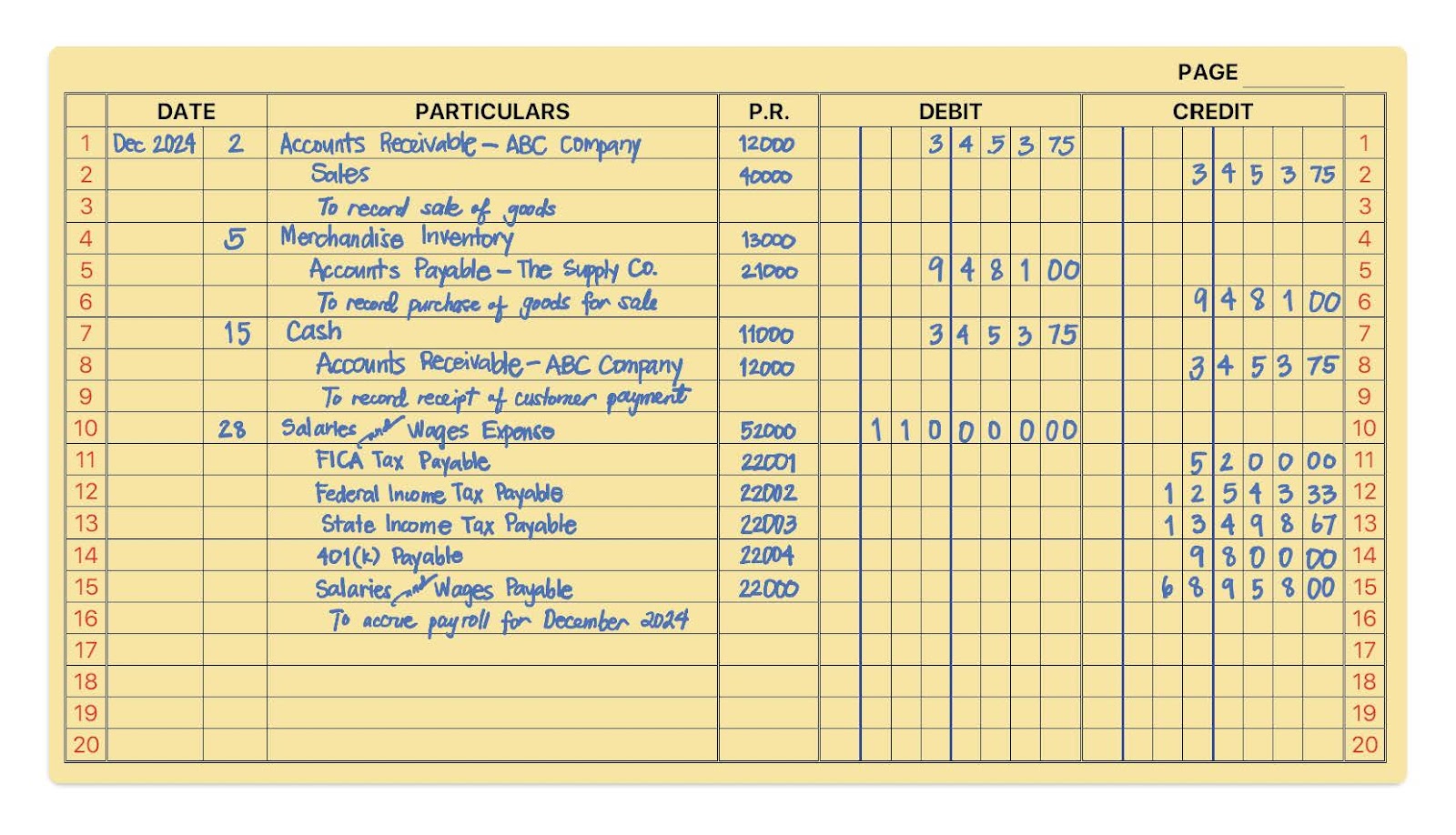

Journal Entries in a Two-column Journal

This kind of journal entry doesn’t exactly look inviting at first glance. All those lines and columns can seem pretty intimidating. But this is how transactions were logged before businesses had computers to handle it all. Imagine the stacks of pages a business would fill up with these entries over a single year. And to make matters worse, there’s no Control+F or Command+F to quickly search for a transaction. If I need to find something specific, I have to flip through hundreds of these yellow pages, one by one, just to track it down.

There’s also no SUM function to test if debits and credits are correct. If I make a mistake in writing a number, I won’t know it right away unless I check if total debits and credits are equal. And if I don’t make it a habit of verifying the equality of debits and credits, mistakes can proliferate and affect the balances of some accounts.

How to Write a Journal Entry

Writing a journal entry is not that hard. What’s hard is analyzing transactions, which we discuss in detail in our guide about debits and credits. Here are the four easy steps in writing a journal entry:

- Write the date first, making sure that it’s the transaction date, not the date you wrote it in the journal.

- Determine which accounts are affected by the transaction. Write the account title in the Particulars column of the journal. Don’t forget to indent credit entries.

- Write the amounts debited and credited in their respective columns.

- Fill out the Post Reference column only when you post the entries in the general ledger. Otherwise, leave it blank for now.

Types of Journal Entries

Journal entries have different types—such as opening, adjusting, and reversing entries. If you have a manual accounting system, knowing these types is essential in daily bookkeeping. However, for accounting software users, the software makes the journal entries behind the scenes. All you have to do is supply the software with the information and instructions needed, and it’ll do the rest.

Here are the different types of journal entries:

Opening Entries

An opening entry is the first journal entry at the beginning of the new accounting period. It carries over the ending balances of permanent accounts from the previous accounting period to the new accounting period. The accountant should refer to the post-closing trial balance to make the opening entries.

Transfer Entries

A transfer entry moves or allocates amounts from one account to another. Usually, they affect accounts within the same class. For example, transferring funds from cash in bank to a restricted cash account requires a transfer entry.

Correcting Entries

A correcting entry corrects errors and mistakes discovered in the books. Correcting entries looks unusual because the accounts debited or credited don’t usually conform to the accounts’ normal balances. For example, if I overestimated an expense, a correcting entry would credit the expense account, which is unusual and something that I wouldn’t see every day.

Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries is needed because businesses using the accrual method record transactions when they happen, not when cash is exchanged. These adjustments help update account balances to show the correct revenues earned and expenses incurred for each period, giving a clear view of the company’s finances.

There are three kinds of adjusting entries: accruals, deferrals, and depreciation adjustments.

An accrual is an item of income or expense that’s recognized even if cash isn’t yet received or paid. Particularly, the two types of accruals are accrued expenses and accrued revenues.

- Accrued expenses are expenses that have been recorded but not yet paid. For example, you might record salary expenses on May 20, even though the payment will be made on May 30.

- Accrued revenues are revenues recorded without immediate cash payment. For example, you might record a receivable on May 5 for services rendered, even though the client will pay on May 15.

A deferral is an item of income or expense where cash has been received or paid but not yet earned or incurred. Deferrals are otherwise referred to as pre-payments. The types of deferrals are deferred expenses (or prepaid expenses) and deferred revenues.

- Deferred expenses are expenses already paid but not yet incurred. For example, if you purchase a one-year fire insurance policy today, the amount you paid is a deferred expense. You’ll recognize the expense gradually as each month passes, reflecting the portion of the policy used each month.

- Deferred revenues are payments received in advance from customers for future goods or services. For example, a landlord may ask a tenant to pay one month of rent upfront to be applied to the last month of the lease. In the landlord’s books, this advance payment is recorded as deferred revenue, as it will only be recognized as earned income in the final month of the lease.

The last (and the easiest) adjusting entry is depreciation. It simply records the periodic depreciation as expense and updates the accumulated depreciation account on the balance sheet. Depreciation adjustments usually are done at year-end.

Closing Entries

Closing entries zero out income statement accounts at the end of each period, resetting income and expenses to start the new period with a zero balance. Revenues and expenses from the previous period transfer to the capital or retained earnings account, capturing the business’s accumulated earnings.

To prepare closing entries, credit accounts with normal debit balances and debit those with normal credit balances. Any difference between debits and credits goes to the income summary, a temporary account used solely for the closing process, ensuring the accounts are clear and accurate for the next period.

Reversing Entries

A reversing entry is made at the start of the new accounting period, which undoes specific adjusting entries to simplify future entries. Though optional, this step is beneficial for preventing double-counting and easing the recording of future transactions.

For example, if wages were accrued at the end of the period, a reversing entry negates this adjustment, so when wages are actually paid, they can be recorded directly without extra adjustments. By reversing prior adjustments, this method reduces errors and streamlines ongoing record-keeping.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

A journal entry is an official record of transactions. It consists of at least one debit and one credit entry.

Journal entries must always be balanced, meaning the total debits must equal the total credits. In other words, any amount entered on one side must have an equal entry on the opposite side to maintain balance.

If a journal entry isn’t balanced, the accounting records will be inaccurate, and the trial balance will show an error. This imbalance can lead to incorrect financial statements and make it difficult to identify and correct errors in the books. To ensure accuracy, every journal entry must have equal debit and credit amounts.

Bottom Line

Accounting journal entries are the foundations of double-entry bookkeeping. Mastering the art of journaling is the responsibility of a bookkeeper, but as a small business owner, you must also take steps to understand how they work. While small business accounting software does away with day-to-day journal entries, bookkeepers and business owners must know how to adjust and reverse journal entries at the end of the period to account for accruals properly.