The last-in, first-out (LIFO) method is an inventory cost flow assumption where the most recently purchased items are considered sold first, directly impacting the cost of goods sold (COGS) on the income statement. This means newer inventory costs are used to calculate COGS, while older inventory costs remain on the balance sheet as inventory.

In this article, I’ll break down how LIFO works, explore its benefits and drawbacks, and show you a comprehensive example of the LIFO inventory method in action.

How the LIFO Method Works

When you’re in a grocery store, you’ll probably grab the item at the front of the shelf—you won’t be reaching for the ones at the back. If we assume the grocery store always restocks by placing new items at the front of the shelf, shoppers will keep picking the newest items while the older stock gets left behind.

That’s essentially how LIFO works: the newest inventory gets used up first, whereas the older stock remains in storage.

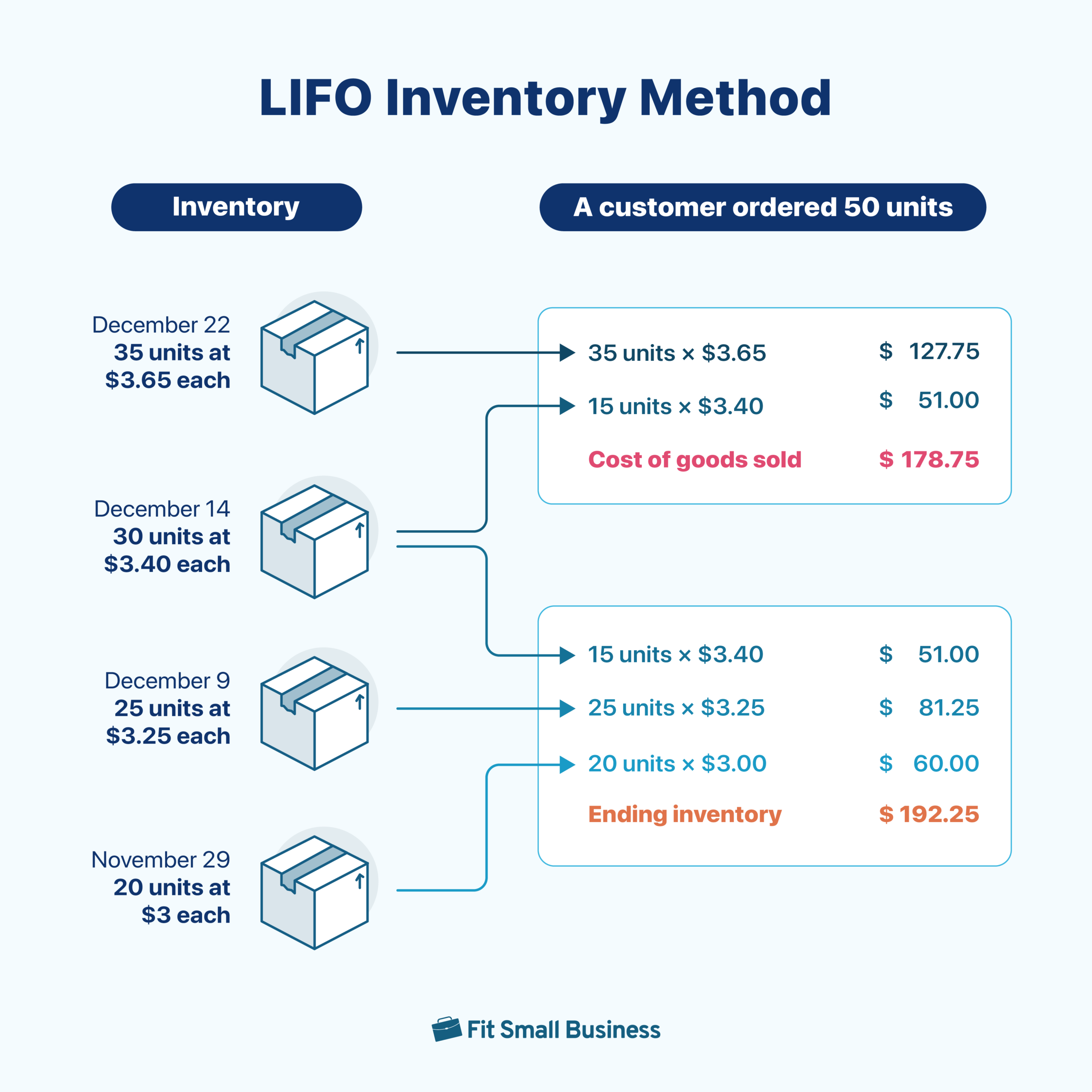

Even if LIFO treats the cost of newly purchased goods as the cost of goods sold first, the items actually sold might not come from those recent purchases. As an example, let’s assume that a customer ordered 50 units from us.

To complete the customer’s order, use the 35 units bought on December 22 first, followed by 15 units from December 14 to fill in the remaining order. The total cost of the customer’s order is $178.75, which is reported as COGS. The remaining units form part of the ending inventory, which consists of the cost of the inventory purchased earlier.

Benefits & Drawbacks of the Last-in, First-out Inventory Method

LIFO is a controversial inventory method because the US GAAP and IFRS principles disagree on using this method. In fact, the IFRS disallows the LIFO method because of its high potential to manipulate profits. But to be fair, I’ll share the benefits and drawbacks of the LIFO method.

Benefits of the LIFO Method

- Short-term increases in profits: LIFO can also influence reported net income through LIFO liquidation. This occurs when a company reduces its LIFO layers by allowing older, lower-cost inventory layers to be included in the current year’s COGS. This can temporarily lower COGS and increase net income.

- Tax savings during inflation: If costs of goods and commodities increase, LIFO reports a higher COGS, effectively reducing taxable income.

- Better matching of revenues and costs: Since LIFO uses the cost of the most recent purchase, it depicts a better matching of current period costs and revenues. Unlike FIFO, which uses the cost of earlier purchases, COGS under FIFO may not accurately reflect the proper matching of current costs and revenues.

In my opinion, LIFO better applies the matching principle. For instance, if inventory is bought and sold in November, the COGS for that month reflects the November purchase cost. On the other hand, FIFO might use older costs, like those from October, which may not match the current sales.

However, I don’t support using LIFO to boost short-term profits. This practice falls into a gray area and can be considered borderline unethical. I strongly advise businesses to exercise caution with LIFO liquidation, as it can raise red flags with the IRS and potentially lead to closer scrutiny.

Drawbacks of the LIFO Method

- Artificial profitability: LIFO liquidation is a double-edged sword. Your profits may be higher because of LIFO liquidation. But this is because you’re simply eliminating older LIFO layers that might have a lower unit cost. Hence, the increase in profit during LIFO liquidation is artificial and doesn’t reflect true performance.

- Complex recordkeeping: LIFO can accumulate multiple LIFO layers that can be ignored for years. These layers won’t go away unless you liquidate them. Hence, recordkeeping under LIFO can be difficult since you always need to keep track of LIFO layers.

- Distorted inventory values: Since LIFO uses the most recent purchases for COGS, the inventory balance on the balance sheet may not reflect current costs. For example, the reported inventory value could be based on prices from one or two years ago, leading to an understated inventory value.

- Mismatched valuation between periodic and perpetual systems: When you use LIFO, you’ll arrive at different ending inventory and COGS balances between period and perpetual systems. LIFO perpetual can undervalue inventory during rising prices, impacting financial ratios and giving a less favorable view of a company’s financial health.LIFO periodic provides a higher, more balanced inventory value, clearly representing the business’s assets. However, this mismatch isn’t true with FIFO because regardless of the system you’re using, FIFO periodic and perpetual will give the same balances.

As a CPA, I am more concerned about LIFO’s ability to manipulate profits, especially with LIFO liquidation. Yes, LIFO recordkeeping can be difficult, but technology nowadays can solve that. In my expert opinion, LIFO should be used ethically to prevent scrutiny from the IRS. I am also concerned about the difference between the LIFO periodic and perpetual systems, as this could impact financial reporting and performance measures.

Global Acceptance of the LIFO Method

In the US, the IRS allows businesses to use the LIFO method for tax purposes as long as they also use it for accounting. But when you look back at the bigger picture, LIFO often gets a bad rap. Opinions about LIFO vary, and based on my experience reviewing industry papers and financial disclosures, I’ve gathered some important points about LIFO.

- Investors and shareholders are concerned about how inventory is valued on the balance sheet under LIFO. Because LIFO often results in lower inventory values, it can make the company’s inventory appear undervalued. This can discourage potential investors who might consider it a red flag when buying the company’s stock.

- Accounting professionals have varying opinions on LIFO. Some find comparing inventory difficult when one company uses LIFO and others don’t. Most accountants are also uncomfortable with the potential income manipulation opportunity with LIFO.

- Multinational companies find it hard to reconcile LIFO inventory with non-LIFO inventory, especially if supply operations are global.

Further reading:

How to Do LIFO in Calculating Ending Inventory and COGS

Being systematic is the key to understanding how the LIFO method works. You have to keep track of inventory numbers in every transaction. However, the way of computation may differ if you’re using the periodic vs perpetual inventory system. Let’s see how they work.

Periodic Inventory System Using LIFO

In a periodic inventory system, you only update the inventory account at the end of the period (e.g., monthly, semiannually, annually) after a physical inventory count. To arrive at COGS, we first determine the cost of ending inventory.

Let’s look at the sample data below as I walk you through the LIFO computations.

Date | Transaction | Quantity | Purchase Price |

|---|---|---|---|

1/1 | Beginning Inventory | 30 | $35 |

1/5 | Purchase | 300 | $36 |

1/10 | Sale | 150 | |

1/15 | Sale | 120 | |

1/20 | Purchase | 200 | $38 |

1/25 | Sale | 250 |

The periodic inventory system requires a physical inventory count at the end of the period. Most companies using periodic inventory systems are small businesses that only count inventory and calculate COGS once per year. However, if you want to use the periodic inventory system monthly, you can estimate the units in the ending inventory without taking a physical count.

For simplicity, let’s assume that the physical inventory count reveals 80 units in the ending inventory.

Under the last-in, first-out assumption, I must remove the goods sold from the most recent purchase. This means the goods in the ending inventory are the earliest purchases. In step one, I know I have 80 units to account for in our ending inventory. Our initial inventory of 30 units—the first LIFO layer—is insufficient to cover the 80 units. Hence, I get 50 more units from the second LIFO layer, the January 5 purchase. Therefore, the cost of ending inventory would be computed this way:

30 units from beginning inventory (30 × $35) | $1,050 |

50 units from January 5 purchase (50 × $36) | $1,800 |

Ending inventory | $2,850 |

The company has two inventory groups: one at $35 per unit and another at $36 per unit. These groups are referred to as LIFO layers.

Now that I know the cost of ending inventory, I can use the COGS formula to calculate our COGS, shown below:

Beginning Inventory | $1,050 | |

Purchases: | ||

1/05: 300 units × $36 | $10,800 | |

1/20: 200 units × $38 | $7,600 | $18,400 |

Cost of goods available for sale | $19,450 | |

Ending inventory (from Step 2) | ($2,850) | |

Cost of Goods Sold | $16,600 |

Perpetual Inventory System Using LIFO

Under the perpetual inventory system, inventory is always updated for every purchase or sale. Under perpetual LIFO, I will do more work keeping the records updated in exchange for having up-to-date information about inventory. Hence, I recommend using perpetual inventory if you have inventory management software.

But if you still can’t afford that, I created a format you can copy and paste into a spreadsheet.

Date of Layer | Units | Cost per Unit | Total Cost of Inventory | COGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

LIFO layers stay in your records for months, if not years. You’ll want to save your spreadsheet as a permanent file to carry from year to year vs starting a new spreadsheet each year.

The process for perpetual LIFO is similar to periodic LIFO, except that I must apply the LIFO rules for each transaction throughout the year instead of waiting until the end. Perform the following steps for each sale during the year:

Date of Layer | Units | Cost per Unit | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

1/1 | 30 | $35 | $1,050 |

1/5 | 300 | $36 | $10,800 |

Total Cost of Inventory Before Sale | $11,850 | ||

As of January 5, I am seeing two LIFO layers. Preparing a schedule of LIFO layers before updating perpetual records for a sale is important to ensure that the cost of goods sold is taken from the most recent layer.

Take note that you must repeat this step before you make entries to LIFO layers if you decide to use perpetual LIFO. This schedule will serve as your guide to what layer needs to be updated.

Date of Layer | Units | Cost per Unit | Total Cost of Inventory | COGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1/1 Beginning Inventory | 30 | $35 | $1,050 | |

1/5 Purchase | 300 | $36 | ||

Sold 1/10 | (150) | $36 | $5,400 | |

Remaining Layer | 150 | $36 | $5,400 | |

Balances as of 1/10 | $6,450 | $5,400 | ||

The sale on January 10 was deducted from the January 5 purchase, the second and most recent layer. I will only use the units in the beginning inventory if the most recent purchases aren’t enough to cover the sale.

I’ll repeat step two to account for the sale that occurred on January 15. There’s no need to update the schedule for any additional purchases because there were none between the sales on 1/10 and 1/15.

Date of Layer | Units | Cost per Unit | Total Cost of Inventory | COGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1/1 Beginning Inventory | 30 | $35 | $1,050 | |

1/5 Purchase | 300 | $36 | ||

Sold 1/10 | (150) | $36 | $5,400 | |

Sold 1/15 | (120) | $36 | $4,320 | |

Remaining Layer | 30 | $36 | $1,080 | |

Balances as of 1/15 | $2,130 | $9,720 | ||

After the January 10 sale, I still have 150 units from the second layer, which is enough to cover the January 15 sale of 120 units. Hence, I will deduct the sale from the second layer.

Afterward, l will extend and foot the totals in the last two columns. As of January 15, we still have 30 units from the beginning inventory and 30 from the January 5 purchase. Our COGS as of this date is $9,720. I didn’t touch the beginning inventory because I know there’s still enough inventory from January 5.

Now, let’s go to the January 25 sale. Since this is a sales transaction, I must first update my LIFO layers before recording anything to help see the status of the layers. The schedule below shows the updated LIFO layers before the January 25 sale.

Date of Layer | Units | Cost per Unit | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

1/1 | 30 | $35 | $1,050 |

1/5 | 30 | $35 | $1,080 |

1/20 | 200 | $38 | $7,600 |

Total Cost of Inventory Before Sale | $9,730 | ||

The sale on January 25 requires 250 units. I know that the January 20 layer only has 200 units, which is not enough to cover the order. That’s why I’m going to the January 5 layer and getting the remaining 30 units. Since we still need 20 units to satisfy the order, we get 20 units from the beginning inventory. Take note of the highlighted portions below to see how I plotted it in the spreadsheet.

Date of Layer | Units | Cost per Unit | Total Cost of Inventory | COGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1/1 Beginning Inventory | 30 | $35 | ||

Sold 1/25 | (20) | $35 | $700 | |

Remaining Layer | 10 | $35 | ||

1/5 Purchase | 300 | $36 | ||

Sold 1/10 | (150) | $36 | $5,400 | |

Sold 1/15 | (120) | $36 | $4,320 | |

Sold 1/25 | (30) | $36 | $1,080 | |

Remaining Layer | - | - | - | |

1/20 Purchase | 200 | $38 | ||

Sold 1/25 (250 units) | (200) | $38 | $7,600 | |

Remaining Layer | - | - | - | |

Balances as of 1/25 | $350 | $19,100 | ||

The total cost of goods sold under LIFO for our January 25 sales is summarized below:

200 units from the January 20 purchase | $7,600 |

30 units from the January 5 purchase | $1,080 |

20 units from the beginning inventory | $700 |

Cost of goods sold for 250 units | $9,380 |

Difference Between Periodic and Perpetual Inventory Systems Using LIFO

Your cost of ending inventory and COGS for the period comes from the schedule with no further adjustments. Notice the cost of inventory and COGS are different under the perpetual and periodic inventory systems since the goods sold come from different LIFO layers.

Periodic | Perpetual | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|

Ending Inventory | $2,850 | $350 | The difference here clearly supports one of the drawbacks mentioned above. Since perpetual inventory updates frequently, inventory costs always reflect the most recent costs at the time of each sale, while periodic inventory only considers the most recent costs from the entire period as a whole. |

Cost of Goods Sold | $16,550 | $19,100 | Perpetual LIFO reports a higher COGS than periodic LIFO. Net income under perpetual LIFO is lower by $2,550 because COGS is high, effectively reducing income tax payable. |

Overall, the perpetual inventory system using LIFO can be tedious. Even if you’re using a spreadsheet, adding new layers and modifying existing layers requires a lot of data entry and cleaning up. Its simplicity is why some prefer the periodic inventory system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

LIFO uses the most recent costs to value COGS and earlier costs to value inventory. On the other hand, FIFO uses the earliest costs to value COGS while using the most recent costs to value ending inventory.

There isn’t an exact formula for LIFO, but you only need to remember that COGS is based on the most recent purchases, and inventory is based on older purchases.

Bottom Line

The last-in, first-out method is an inventory cost flow assumption allowed by US GAAP and income tax laws. Proponents of the LIFO method argue that it improves the matching of revenues and replacement costs. However, the cost of ending inventory in the balance sheet presents older costs. More importantly, users of the LIFO method say that it gives them tax savings since they report a lower taxable income.