When processing payroll for yourself vs employees, choosing the right business structure is key to minimizing taxes. Determining how much and how often to pay helps with managing profitability and cash flow, which is why setting up a self-employed payroll system is important. The easiest approach is to work with a reputable payroll service—it can make self-employed payroll easier while supporting you with tax law compliance.

However, if you aren’t ready for a service just yet, we’ll also cover the steps on how to set up payroll for self-employed individuals. They are:

Step 2: Determine how much to pay yourself

Step 3: Set your pay frequency

Step 5: Enter and review hours worked or salaried wages

Step 6: Approve and process payroll

If you need an easy way to automate payroll and file payroll taxes, consider using Gusto. While payroll software isn’t necessary if you only pay yourself, as your team grows, you can pay your employees as often as you’d like (weekly, biweekly, or monthly). The software can be set up in a few days, and you can pay through direct deposit.

Note that sole proprietors and partners cannot be employees of their business, and therefore never receive a paycheck. This also includes LLCs that have not elected to be taxed as a corporation. The only time sole proprietorships or partnerships would need a payroll service is if they have employees who are not owners.

Self-employed Payroll Providers

When choosing a payroll software, employers must consider their HR and pay processing needs. The business’ structure, benefits you want to access, and available software integrations should all be considered when selecting a payroll provider. Cost is also a top factor, making it essential to analyze all the needs of a business before making a final decision.

While we found Gusto as the best overall option for self-employment payroll, we also provided a few other great options in the table below that may be a better fit based on your employee payroll needs.

Self-Employed Payroll Service | Best For |

|---|---|

LLCs with S-corp tax status that need to automate regular salary payments and owner’s draws | |

Sole proprietorships with non-owner employees who want to integrate payroll with existing QuickBooks accounting solutions | |

Retail business owners needing to pay contractors in addition to themselves | |

Nonprofit owners needing a cheap full-service payroll option that handles payroll taxes | |

S-corp owners wanting the business to subsidize their health insurance through payroll | |

Solopreneurs looking for payroll support with incorporation services and a solo 401(k) plan |

How to Process Self-employed Payroll in 6 Easy Steps

Step 1: Choose Your Business Type

Before determining how much business income to distribute to yourself, it’s a good idea to spend time contemplating how to structure your business if you haven’t already. Your business structure—sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation—should form the basis of all payroll decisions you make regarding how to pay yourself. You could save thousands of dollars in taxes and avoid audits from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) if you set your business up correctly.

Did You Know? The IRS considers an individual as self-employed if:

- You do business or carry on trade as a sole proprietor or an independent contractor

- You are a member of a business partnership

- You have your own business, which includes running a part-time business or offering your services as a gig worker

And remember, if you’re running a sole proprietorship with no employees (and it’s not an S corporation), these steps will not apply to you—your income will flow directly to your personal income tax return, meaning you can use as much or as little of the profits for personal reasons as you’d like. Plus, you won’t need to file a separate tax return for your company or comply with business payroll laws.

If you or your accountant have already completed the paperwork to determine your business structure, take time to learn the different options and responsibilities you have in regard to processing your own payroll.

A sole proprietorship is a business that has a single owner. It requires little to no paperwork, and all taxes are passed down to the owners’ personal tax return. There is no personal liability protection, so customers could sue the owner if issues arise.

There are pros and cons to a sole proprietorship, but with this structure, you can pay yourself a draw as often as you want. An owner’s draw doesn’t affect your taxes but merely reduces your capital investment in the company. The draws are not subject to the 15.3% self-employment tax, but the business net income is whether or not the funds are withdrawn.

Don’t have a business bank account yet? Check out our guide for help opening a sole proprietorship bank account.

A business partnership is a business that has two or more owners. A partnership agreement governs how the owners divide profits and losses, and all taxes are passed down to their personal tax returns.

In a partnership, each partner is only responsible for reporting their agreed-upon percentage of taxable income. Partners do not receive paychecks, but rather draw money out as desired, similar to a sole proprietorship. There are no employee or employer taxes, but the earnings are subject to self-employment taxes. Partners can also agree to guaranteed payments, which are predetermined draws that are subtracted from partnership income before applying each partner’s profit-sharing percentage.

A Limited Liability Company (LLC) provides liability protection to owners in the event of a lawsuit.

Members of an LLC aren’t employees and don’t receive payroll for a salary (unless the LLC chooses to be taxed as a corporation). For tax purposes, LLCs with one owner are treated like sole proprietorships—owner’s draw—and multi-member LLCs are treated like partnerships—distributions or guaranteed payments. However, you can opt to recognize an LLC as an S-corp or C-corp for tax purposes to have more beneficial payment options.

An S-corp can range from a small to a large business and provides protection from personal liability. Compensation for services must be paid to owners through the regular payroll system, including the withholding and payment of payroll taxes. Any income left in the S-corp will be taxable on the owner’s return for income taxes, but no self-employment tax is due.

Any S-Corp owner who performs substantial services for their business must legally be classified as a regular employee. You’ll avoid the 15.3% self-employment tax (12.4% for Social Security and 2.9% for Medicare), but any income left in the S-corp will be taxed on your (the owner’s) return for income taxes.

A C-corp is usually a large business that issues stock to raise money and has a board of directors that governs company decisions. Owners are protected from personal liability, but it’s costly to get started and requires extensive paperwork. Earnings are double-taxed when absorbed by the C-corp and when distributed to owners. C-corps are separate entities and not for the self-employed.

Similar to S-corp owners, owners of a C-corp must pay themselves a reasonable salary for any services they provide to the company. Any taxable income left in the corporation after salaries are distributed is subject to income tax on the corporate tax return. In addition to any salary received, the owner includes any dividends received as income on their personal return.

Step 2: Determine How Much to Pay Yourself

The primary payroll concern for many entrepreneurs is how much to pay themselves. However, before going into the amount, consider the payment options, as these vary depending on your company’s business structure. (We’ll provide more detail on payment types below.)

Business Structure | Nontaxable Distributions | Salary | Taxable Dividend | Guaranteed Payments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sole Proprietorship | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Partnership | N/A | N/A | N/A | ✓ |

LLC (not elected as a corporation for tax purposes) | ✓ Single-Member and Multi-Member | N/A | N/A | ✓ |

S-corp | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A |

C-corp | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | N/A |

Once you’ve evaluated the different business structures and how you can pay yourself with each, decide how much you’re worth to the business. If your business is a sole proprietorship or partnership, you can pay yourself any amount—from $100 to $10,000 a month. If it’s an S-corp or C corporation, and you opt to classify yourself as an employee, the IRS requires your salary to be “reasonable.”

In determining what a reasonable self-employed payroll salary is, consider the market rate for the services you’re providing to the company. Check popular job sites for related job posts, as these sometimes list pay rates—or you can also use a salary comparison solution (check out our list of best salary comparison tools for options). Underpaying or misclassifying yourself as an employee or nonemployee can lead to an audit and additional taxes and fees.

When you have more autonomy in determining how much to pay yourself, keep in mind that the pay should still be reasonable to allow your business to continue growing. You should avoid paying out all of the income in case of emergencies. Consider how much your contributions are worth to the company, the type of work you’re performing, and the total profits coming into the business.

Step 3: Set Your Pay Frequency

Typically, you can pay yourself as often as you’d like—but it’s a good idea to set a consistent pay period or pay frequency to keep the process organized. If you’re taking owner draws or distributions, you may want to pay yourself less often until you have enough experience with the flow of business income; seasonality can cause low cash flow during certain periods.

If you classify yourself as an employee of your business, you should pay yourself more often to align with the practices of other employers. Guaranteed payments for partnerships should be structured according to the original agreement between the partners—for instance, monthly minimum payments should be settled by the end of the month.

Step 4: Set up a Payroll System

After determining how often to pay yourself, you’ll be ready to set up a payroll system to help with automation and compliance. You can use online payroll templates to give you access to automated calculations. Setting yourself up in the system shouldn’t require much time; you’ll enter your name, Social Security number, and so on. If you want direct deposit, you’ll submit bank account information.

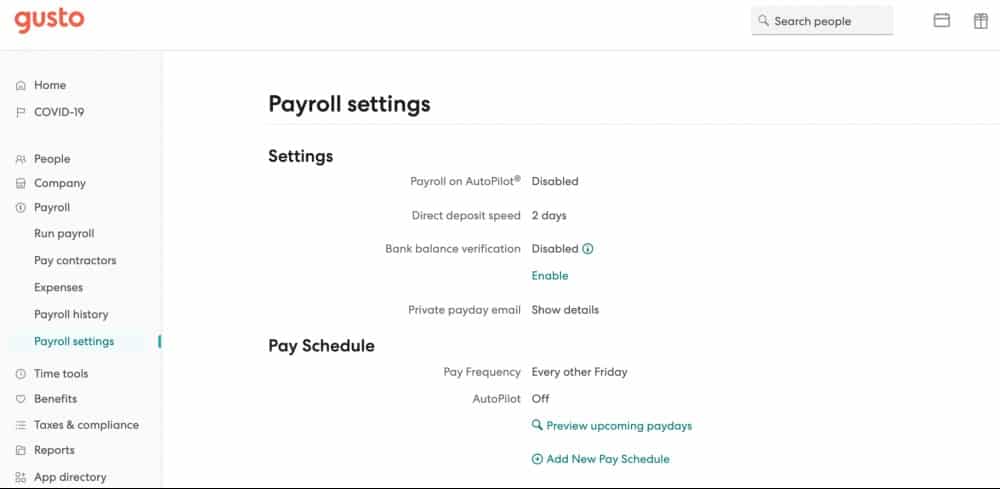

If you choose to run payroll with software like Gusto, you can set your self-employed payroll to run on autopilot.

By default, Gusto’s Payroll by AutoPilot feature is disabled; most employers enable it once they’ve set their regular payment amount or rate.

Gusto will run payroll for you automatically two days before your payroll deadline. If you decide to classify and pay yourself as an employee, Gusto will withhold and remit your employee and employer payroll taxes—without any required action from you. To learn more, visit the website for a free demo.

If you won’t be using a full-service payroll or an accountant, you can either file quarterly using Form 1040-ES or pay in one lump sum by April 15 of each year. Read our Ultimate Guide for Independent Contractor Taxes for more information about self-employment taxes.

Step 5: Enter & Review Hours Worked or Salaried Wages

Regardless of which payroll system you use, you’ll need to either monitor hours worked (you can use our free timesheet to track this) or salary due per period in addition to work performed. If you’re receiving payment as an employee, you should have a solid foundation on which to form your wage calculations.

Annual salaries are based on what the market is paying and how much work you do; divide the total salary by the number of pay cycles in the year to calculate how much you should receive each period.

An owner’s draw, distribution, and dividend payment don’t require as much justification as a salary payment. Neither does a guaranteed payment for a partnership, although you can deduct it from taxable business income. You’re not required to perform any valuable services on behalf of the business to be entitled to any of these funds; you can withdraw funds simply because you’re the owner.

Step 6: Approve & Process Payroll

Once you’ve documented and reviewed what you’re planning to pay yourself, you can approve and process it using the tools available to you. Online payroll systems typically have a page that allows you to click “approve” or submit before funds are disbursed.

Keep in mind that gross pay should be the same as net pay for any non-salary payments on your self-employed payroll, meaning there won’t be any tax payments withheld. As for paying a salary, you should see the appropriate amounts withheld for self-employment taxes and benefits like for a solo 401(k), if applicable.

Most payroll payments are made via check or direct deposit. If you’re not yet using payroll software, you can print payroll checks free online. All you need is a magnetic ink cartridge, printer, and payroll check stock. Of course, direct deposit is the most convenient option since money is deposited in your bank account within two to four business days. Pay cards are another option.

A Deeper Dive Into Self-employed Payment Types

Payroll for self-employed business owners can work in multiple ways, but ultimately, the process still includes determining how to pay yourself and doing it. The primary concern is ensuring the way you compensate yourself is legal and cost-efficient.

Once you know how much to pay and how often to distribute payments, you’ll set up a fool-proof payroll system that involves pay calculations and a transfer of funds into your possession. There are different ways to process this transfer of funds, but determining the best way depends on your business type.

There are several ways to pay yourself, and although they may all seem the same to you, the IRS treats them differently at tax time. Depending on how your business is organized, you may be better off paying yourself an owner’s draw, a regular salary, dividend, distribution, guaranteed payment, or a mixture thereof.

A draw is money taken out of a business for personal use by the owner—usually sole proprietors or single-member LLCs—that can’t be written off as a business expense. Unlike regular salary payments, a draw is not considered a payroll expense and isn’t subject to withholding taxes or federal and state income taxes.

The only businesses that are eligible to take owners’ draws are sole proprietorships. Partnerships operate similarly but, because there are multiple owners, the withdrawals are called partnership distributions (distributive shares). The most important factor to remember about owners’ draws is that they don’t operate like salary payments, meaning they cannot be deducted as expenses to reduce taxable income.

Regular salary payments are for owners classifying themselves as employees—for instance, with S-corps or C-corps (sole proprietors and partnerships don’t have this option). If you opt for a regular salary, you must reduce your salary payout by any payroll deductions, such as health insurance and withholding taxes like FICA. Your business must then remit the withholdings along with employer payroll taxes on your wages to the appropriate tax agencies.

Guaranteed payments are set up by partnerships to ensure the owners receive a minimum amount of business income for the period, regardless of how much income the business reports. A partnership distribution is the allocation partners agree upon regarding how to split the company’s total profits and losses; for example, 50% and 50%. S-corp owners can take distributions as well. A guaranteed payment is a specific dollar amount each partner must receive while partnership distributions are usually set percentages.

Guaranteed Payments and Distributions Example

Bill and Jennifer made an agreement that includes a 50/50 net profit divide for each year. This year, the business earned $30,000, which equates to $15,000 for each partner. This is a partnership distribution (as long as the partnership actually pays out the cash). The agreement also includes a $20,000 guaranteed payment for Jennifer, who brings years of experience to the business that Bill doesn’t.

The $20,000 guaranteed payment reduces the partnership taxable income before the profit sharing percentages are applied. Partnership taxable income after guaranteed payments is $10,000 and split 50/50 between Bill and Jennifer. In this scenario, Jennifer will receive cash and an income of $20,000 for the guaranteed payment. She will also receive another $5,000 of income and may or may not choose to receive a distribution for that amount. Bill will receive $5,000 of income and may or may not choose to receive a distribution of that amount.

This guaranteed payment isn’t a salary, so payroll taxes aren’t withheld; however, the company can write it off as a business expense, reducing taxable income for the business. However, the owner who receives a guaranteed payment will be subject to self-employment taxes. On the contrary, a business cannot write off a partnership distribution, so taxable income will include all money paid to the owners; the owners will pay taxes on the gross profit.

Dividends are regular payments made to a C-corp’s shareholders out of profits the business earns. These payments are typically paid in cash, like distributions, but can also be distributed as additional shares of stock. They’re divided according to the total stock a shareholder owns in proportion to the total stock outstanding. If you own 25% of the available stock, you’ll receive 25% of declared dividends. In addition, the dividends are taxed.

One attribute owners enjoy about paying themselves in dividends is that they can typically be taxed at a lower rate than their regular salary, potentially saving up to 20% in taxes. Partnerships and LLCs don’t pay any taxes on distributions, but the owners are subject to self-employment taxes when their share of the earnings is passed down to their personal tax returns. S-corps can issue tax-free non-dividend distributions to owners as long as they don’t exceed their equity in the company.

It’s important to understand the basic payment types available for self-employed payroll processing. Often, business owners assume they can withdraw money from the business however they want—only to be charged excessive penalties and taxes for not complying with applicable laws. We encourage you to do additional research in addition to consulting with a tax adviser before finalizing your new self-employed payroll processing system.

Self-employed Tax Rates

Self-employed tax covers Social Security and Medicare contributions, typically at a rate of 15.3% of your net earnings. Aside from this, self-employed individuals may also be responsible for paying federal, state, and local income taxes.

State and Local Taxes

Aside from federal taxes, you may need to pay state and local taxes as a self-employed individual. State taxes generally include:

- State income tax: Most states require you to pay income tax on your earnings, though rates and rules differ.

- Business taxes: Depending on your business structure and state, you may need to pay additional taxes, like franchise taxes or gross receipt taxes.

- Registration and licensing: Many states require self-employed individuals to register their businesses and obtain necessary licenses or permits.

- Property taxes: If you use part of your home for business, this might affect your property assessment.

- Sales tax: A consumption tax imposed on the sale of goods and certain services at the point of purchase.

- Use tax: It is complementary to the sales tax and imposed on the use, storage, or consumption of taxable items or services on which no sales tax was paid.

When Self-employed Taxes are Due

Generally, you need to file an annual income tax return. But since taxes are not automatically withheld, you’ll likely need to make quarterly estimated tax payments to avoid penalties. The IRS has established specific due dates for quarterly estimated tax payments.

Quarterly Period | Filing Due Date |

|---|---|

January 1-March 31 | April 15 |

April 1-May 31 | June 15 |

June 1-August 31 | September 15 |

September 1-December 31 | January 15 (the following year) |

Self-employed Payroll Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Yes. A self-employed individual works for himself while a freelancer works for a client. With that in mind, there is also a difference between how they are paid and taxed.

According to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), self-employed high earners are required to pay an additional 0.9% Medicare tax. Self-employed high earners, as defined by the ACA, are individuals who earn more than $200,000 or couples earning more than $250,000 and filing jointly.

Self-employed individuals, including those who are classified as freelancers or small business owners, should report their FICA taxes using Form 1040 Schedule SE.

Bottom Line

There are many factors to consider when doing payroll for self-employed entrepreneurs—most importantly, business structure. You could easily end up paying more than a thousand dollars extra if you neglect to pay yourself a reasonable salary from an S-corp or forget to make payments to cover your sole proprietorship’s self-employment taxes.

If you’d like to try a payroll software service that will pay you with little to no effort from you on the back end, consider Gusto. Once you set up the amount you want to be paid and the frequency, Gusto will handle the rest. With the click of a few buttons, you can set payroll to run on autopilot. Sign up for a payroll plan today.

Disclaimer: Fit Small Business does not operate as a licensed legal or tax professional. We recommend you consult with your lawyer, payroll accountant, or licensed professional for decisions related to your payroll process.